Launch of ILO Toolkit- Forced Labour and Fair Recruitment.

|

WEBINAR TO LAUNCH THE ILO TOOLKIT FOR JOURNALISTS Thursday 30 July 2020 from 14:00 – 15:15, |

|

WEBINAR TO LAUNCH THE ILO TOOLKIT FOR JOURNALISTS Thursday 30 July 2020 from 14:00 – 15:15, |

World Day against Trafficking in Persons- 30 July 2020.

As we prepare to mark this year’s World day against Trafficking in Persons,

|

106th World Day of Migrants and Refugees (WDMR), 27 September 2020. |

Gabriella Bottani, Talitha Kum international coordinator speaks about Victim-centred approaches to investigations and prosecutions– addressing the 20th OSCE Alliance against Trafficking in Persons Conference 20 – 22 July 2020.

Chairperson of the OSCE Permanent Council Ambassador Igli Hasani (l) and the OSCE Special Representative and Co-ordinator on Combatting Trafficking in Human Beings Valiant Richey address the closing of the 20th Alliance Conference,

Prosecute human traffickers and deliver justice to victims: 20th OSCE Alliance Conference against Trafficking in Persons (20 -22 July 2020) calls for an end to impunity.

UN announce the appointment of a new Special Rapporteur on Trafficking in Persons.

Congratulations to Professor Siobhán Mullally, Director of the Irish Centre for Human Rights at NUI Galway,

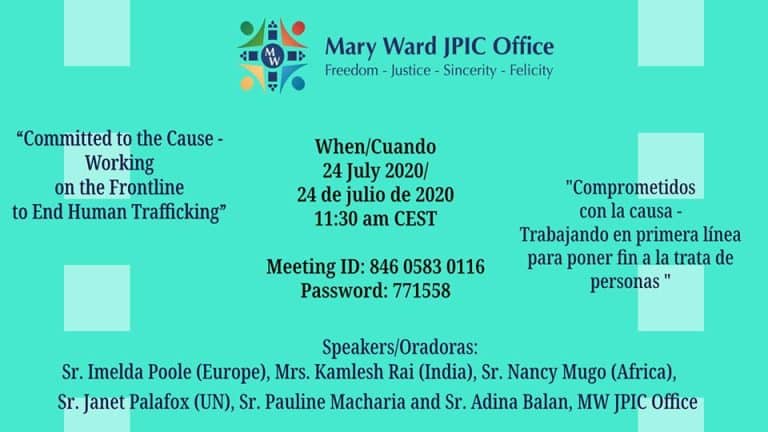

Join Mary Ward JPIC Webinar Friday 24 July 2020 @ 11:30 CEST (10:30 UK time).

Committed to the cause: Working on the frontlines,

For those of you who missed the International conference ‘’Implementing and going beyond the PALERMO PROTOCOL’’ held 29/30 June last, you can follow a recording of the third session,

Online Webinar via ZOOM:- Presentation of Findings of the ODIHR and UN Women Policy Survey Reports and Recommendations “Addressing Emerging Human Trafficking Trends and Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic”